We all have cherished belongings: a photo of your children, a beloved relative’s ashes. These things are treasured, no matter where you live. So why doesn’t the law protect the belongings of unhoused people?

A new report by UBC, SFU and University of Ottawa researchers found the personal property rights of unhoused people in Canada are systematically undermined. Co-authors Dr. Alexandra Flynn (AF), associate professor in the UBC Peter A. Allard School of Law, and Dr. Nicholas Blomley (NB), professor of geography at SFU, discuss why belongings, and adequate housing for all, matter.

Why belongings?

AF: Belongings encompass so many different parts of who we are. This could be things you need for survival, like medication, government ID, or a sleeping bag and tent. It could be things you need for your work, like a suit, a computer, or for some unhoused people, a shopping cart or bike to collect recyclables. Or it could be treasured belongings that have no monetary value but mean everything to the person: a photo of my baby with his big brother, for instance, or things my Mom gave me.

NB: Unfortunately, different rules apply for people who are unhoused compared with those who have a place to live. Dismantling a tent means you’re taking away the things someone owns. If you’re a person who doesn’t have control over your space, there is nowhere you and your belongings can be where you won’t be governed by forms of control or regulation.

We heard time and time again in interviews for this report that unhoused people are used to their belongings being seized—one person had their relative’s ashes taken from them—and they lose a part of what makes them themselves.

What does the law say?

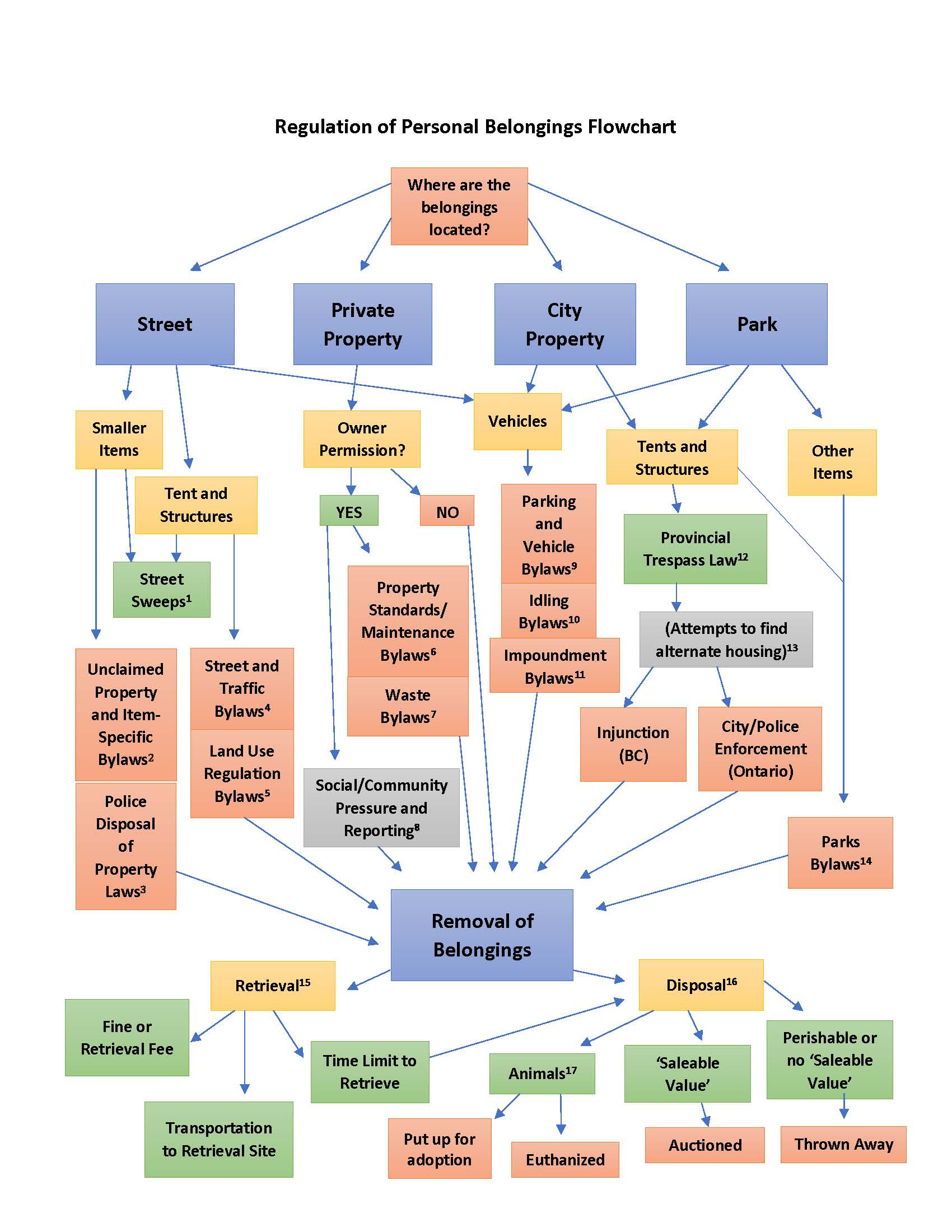

AF: We looked at case law, regulation, and spoke to people in Ontario and B.C. from 2019 on, and found that a hodgepodge of laws exists which ultimately allow seizure and destruction of unhoused folks’ belongings. As a result, people often end up having to carry their belongings with them all day, every day.

This visibility puts them at even greater risk of regulatory action, which is often based on stigma within the law that allows enforcers to make value judgements on people’s belongings. Words like ‘garbage’, ‘unmarketable’, ‘offensive’ and ‘worth under $500’ are used. But value is subjective. What ‘value’ do my priceless photos of my children hold to other people?

These laws also disproportionately affect those who are Indigenous, given a disproportionate number of Indigenous people experience homelessness and poverty due to the effects of colonialism.

Destroying vital belongings like medicine, tents, sleeping bags, IDs, and documents forces unhoused people to replace them, which is costly and often impossible.

NB: That’s not to mention the mental health harms involved. There’s a sense of being devalued, of you and your belongings being treated as less-than—which they are because they’re not being protected.. These laws criminalize poverty and exacerbate the condition of homelessness by inflicting trauma, which can lengthen homelessness.

And there’s not much unhoused people can do to get their belongings back or be compensated for their loss, because the laws are complex and require navigating bureaucracy—that’s if the belongings have not been destroyed immediately.

What is the solution?

AF: We need to recognize that unhoused people have property rights. Just like all property rights, there need to be remedies, like prevention, compensation, and punitive actions against those who seize property without the right to do so. There are short-term solutions: Municipalities can and must give notice, and options for people to safeguard their belongings close by. But the real remedy is housing.

NB: The best solutions, we feel, are those that are based on the experience and wisdom of unhoused people themselves. We encourage policy-makers to first sit down with unhoused people first, and listen carefully.

Our stuff matters to all of us, whoever we are. And I think at one level we can all hopefully understand that.

Interview language(s): English

For more information, visit the SFU website. A launch event will be held on Nov. 2, 2023 and recordings will be available.

For interviews with Dr. Flynn, contact alex.walls@ubc.ca. For interviews with Dr. Blomley, contact melissa_shaw@sfu.ca.

This story was originally posted on UBC News.