Amending British Columbia’s Land Act: Effecting Reconciliation and Increasing Efficiency of Project Permitting

Eric Murphy

Allard JD Graduate 2024

Jun 25, 2024

Project development is integral to British Columbia’s future. Massive near-term infrastructure development is needed to meet BC’s electrical energy goals. Demand for BC mining products is increasing as the world transitions to cleaner forms of energy that are dependent on critical minerals. Although BC is well-situated to meet this need, permitting requirements slow development by years, if not decades. Permit issuance engages the government’s duty to consult with potentially affected Indigenous communities, and project proponents are rightly concerned that inefficiency in discharging this duty is slowing development.

Amending the Land Act

Recently proposed amendments to British Columbia's Land Act would have allowed the Province to negotiate agreements with Indigenous groups that might require project proponents to obtain their consent before pursuing development.

Instead, the proposed amendments were retracted after facing severe criticism. Critics worried that the amendments would risk granting a broad veto power to Indigenous groups over project development throughout the province, unreasonably fail to balance interests, stall development, affect existing tenures, and subject project proponents to exploitative impact benefit agreements in an unprecedented upending of the current system. The concern was that the proposed amendments would “go much further than the Supreme Court of Canada’s rulings… [on] Aboriginal rights”. This appears misguided in its appreciation of the scope of entitlements already made available through the Crown’s duty to consult with affected Indigenous communities.

If this criticism is driven by a misunderstanding of current law, two questions should be addressed by future proposed amendments to the Act:

Would a power to negotiate such agreements increase the scope of already existing requirements under the duty to consult, and

What limitations on the power to negotiate such agreements should be included in proposed amendments to the Act?

Current law on requiring consent, veto powers, and the duty to consult

The duty to consult has its foundation in the Constitutional affirmation of rights of Indigenous peoples and jurisprudence from the Supreme Court of Canada, rendering it as unassailable as these bedrock authorities. The duty to consult arises where Crown activity potentially affects Indigenous interests. Proportionate to the strength of the Indigenous claim and severity of infringement, the duty ranges from mere outreach to full accommodation. Recent legislative invocation of the consent-focused United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples suggests that British Columbia is moving towards the accommodative end of this spectrum.

Consent requirements resulting from this duty appear most prominently in the Supreme Court of Canada case Tsilhqot’in Nation v British Columbia, where Aboriginal title was found. Aboriginal title entails a consent requirement.

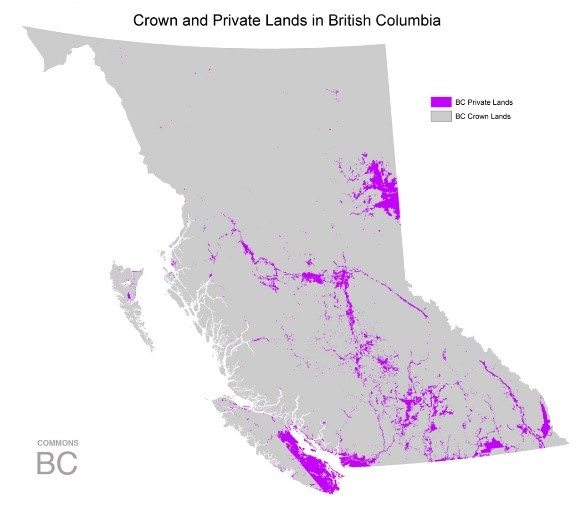

Critics are correct to point out that almost all land in British Columbia is Crown land and potentially subject to a duty to consult. It could be unreasonable to impose a consent requirement in areas where the rights or title claim is not far enough towards the deep end of the consultation spectrum. It could also be necessary to enforce a consent requirement where the duty requires deep consultation since requiring consent is explicitly within the potential scope of the duty to consult in cases of serious rights infringing development for claims at the deep end of the consultation spectrum.

Judicial review

Negotiated agreements would be instances of delegated authority and subject to judicial review. Identifying an appropriate limit to the scope of negotiated agreements to ensure that consent requirements are not unreasonably imposed by unduly exceeding the strength of the right or title claim at issue would likely be a determinative factor in judicial review of negotiated agreements. If future proposed amendments made this limit more explicit it could give industry some certainty that the Province would not be able to unreasonably enter into sweeping consent requirement agreements, allaying concerns respecting the high percentage of British Columbia subject to consultation requirements.

Existing tenure

Existing tenures are subject to consultation requirements upon renewal, but renewal without substantive change does not trigger a fresh consultation duty. A negotiated agreement under an amended Act which changed existing tenure conditions, particularly those subject to renewal, would likely only be reasonable if it aligned with the original strength of the claim under the duty to consult spectrum analysis. It seems likely that such an agreement would not exceed the scope of the consultation already discharged, but explicit reference to this in a future proposed amendment could give industry confidence that existing tenures would not be unreasonably affected.

Development and impact benefit agreements

The current system demands a haphazard tripartite negotiation between private proponents, Indigenous groups, and the government. Government must discharge its duty to consult, but in practice, this is achieved through negotiated Impact Benefit Agreements between Indigenous groups and private proponents.

Where there is Indigenous opposition to development, consent requirements which are already available demand a costly and inefficient court process to enforce, to the detriment of all involved. This could be avoided by the Province recognizing appropriate consent requirements through negotiated agreements under an amended Land Act

Many Indigenous groups are not averse to development. It could be helpful to both Indigenous groups and proponents to provide the Indigenous groups more latitude, where commensurate with the strength of their rights and title claims, to assure the industry of their willingness to negotiate a consent-based agreement. The Indigenous group would benefit from exercising agency over rights to which they would otherwise have been entitled in a consultation analysis, and the proponent would benefit from the increased efficiency of the deal. There is no reason to suspect that the kind of impact benefit agreement required to reach consensus would be substantially different from those which are already required under the current system, so long as the agreements negotiated by the Province do not award consent requirements where they would not be otherwise engaged under a duty to consult framework.

Conclusion

The central concern regarding the recently proposed amendments seems to be that agreements negotiated under the amended legislation could risk granting consent requirements where the duty to consult would not otherwise impose them. Such agreements would however likely be found unreasonable on judicial review. The Constitution, Supreme Court of Canada jurisprudence, and existing legislation clearly support that where there are strong claims at the deep end of the consultation spectrum, enforceable rights up to and including requiring consent already exist. This makes it difficult for government to discharge its consultation obligations while encouraging development, handicaps pro-development Indigenous groups in negotiating with proponents for fair deals, and puts an undue burden on anti-development Indigenous groups with strong claims under the consultation framework. This frustrates industry by slowing development through a lengthened permitting process. Future proposed amendments should include guidelines to ensure that the negotiated agreements align with the scope of the duty to consult framework, which is more favourable to Indigenous groups’ negotiating position than some proponents perhaps realize or desire.

Allowing negotiated agreements between the Province and Indigenous groups regarding consent requirements could dramatically increase the efficiency of discharging the duty to consult and speed project development. Adopting this new framework is highly precedented as it would not necessarily exceed the bounds of what already functions as legal reality in Canada. Perhaps, with corresponding limits to give assurance to industry, a future attempt to amend the Land Act to align with the spirit of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples will not raise as many hackles the second time around.

- Centre for Law and the Environment