Rethinking the Reception of English Law in British Columbia

Gabrielle Matheson

Allard JD 2022

Jun 21, 2021

In 2013 the Supreme Court of Canada held that a 1731 English statute requiring all documents filed in court proceedings to be in English was in force in the province of British Columbia. The Court held that the statute met the requirements set out by BC’s provincial statute governing the reception of English law in BC: the criminal and civil laws of England as of November 19, 1858 are received in the province “so far as they are not from local circumstances inapplicable.”

If the idea of a court declaring in 2013 that a 1731 English statute is in force in Canada makes you uneasy, you might understandably be forgiven for having some questions: Are there other ancient English statutes lying in wait to be declared in force in BC? Just how wide is the crack created by the phrase “not from local circumstances inapplicable” that these statutes might slip through? And how is it possible that uncertainty about what laws are currently in force in BC has persisted after more than 150 years of legislative and judicial activity?

These are some of the questions I researched as a fellow of the Centre for Law and the Environment. This project, which I conducted with the Centre’s director, Stepan Wood, invites critical reflection on the historical and contemporary reception of English law in BC with the objective of rethinking reception as an important site for legal reform. Our research examines prevailing approaches to reception in Canada to better understand the legal effect of some historical developments that scholars, courts, and provincial legislatures may have overlooked.

Namely, BC and Ontario conducted careful reviews of English statute law as part of their late-nineteenth century efforts to revise and consolidate the laws in force in their jurisdictions. Historical records suggest that these reviews were intended to settle the question of which English statutes were in force, so that the citizens of the province or territory would be able to know with certainty the laws to which they were subject.

The BC legislature commissioned such a review as part of its preparation of the 1897 Revised Statutes of British Columbia (RSBC 1897). This review resulted in the adaptation and incorporation of more than 150 English statutes into BC’s statute books, from the 13th-century Magna Carta to the Sale of Goods Act, 1893. Notably, the aforementioned 1731 Statute was not included in the 1897 Revision. If we are right that BC’s 1897 review and consolidation of English statute law was intended to be exhaustive, then the 2013 Supreme Court of Canada case mentioned above was wrongly decided.

Over the summer of 2020 and through the 2020-21 academic year, Dr. Wood and I dug through a mass of archival material dating from the 19th and early 20th centuries. This research was complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as we could not consult archival materials available only in hard copy. Fortunately, a significant amount of archival material has been digitized, and was available to us online. Toward the end of the school year we were able to visit the provincial archives and legislative library in Victoria and the BC courthouse library in Vancouver, but we only scratched the surface of their collections.

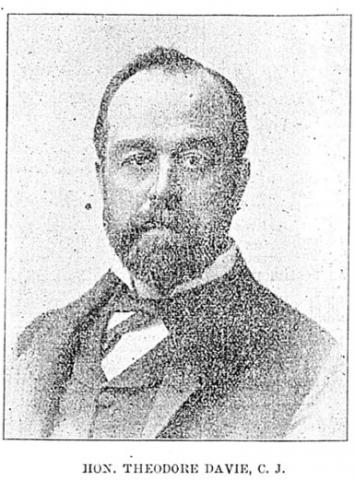

Newspaper articles, Commissioner’s Reports, Journals of the Legislative Assembly of BC and provincial jurisprudence from around the time indicated that in scope and scale the RSBC 1897 was unlike any statutory revision or consolidation the province had undertaken before. It was the first time the BC legislature tasked a Revision Commission with revising and consolidating not just provincial but also English statute law and was the only revision to conduct a review on such an exhaustive scale. This Commission was led by Theodore Davie, an individual particularly well-equipped for the task as Chief Justice of BC at the time and a former provincial premier and Attorney General.

Just as important as our archival research was determining how scholars and courts have treated the 1897 Revision subsequent to its completion. Numerous key English statutes commonly accepted as in force in BC were explicitly incorporated in the RSBC 1897. But neither the courts nor academic commentators appear to have considered the legal effect of the RSBC 1897 on the reception of English statute law.

This silence and resulting uncertainty about the legal effect of provincial consolidations of English statutes are typical of the caselaw and scholarship on the reception of English law across Canada. The approach to reception in Canada is different province to province, complicating the determination of the applicability of English law. In Alberta and Saskatchewan, English law was received only if it was “applicable” to the province, which subtly contrasts with the “not inapplicable” threshold in BC. Ontario’s statute makes no reference to applicability, while in Nova Scotia there is no statute governing reception at all. Ontario appears to be the only other province that conducted a review and consolidation of English statute law comparable to RSBC 1897, but similarly little mention is made of its legal effect in judicial decisions or scholarly commentary.

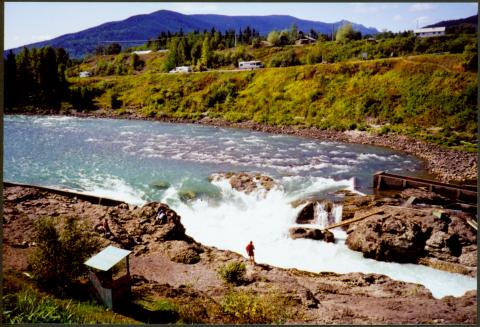

What does any of this have to do with the environment, you might ask? Past and future decisions on the reception of English law in Canada have potentially far-reaching implications for environmental and Indigenous law. For example, the Supreme Court of Canada has used the doctrine of reception to deny Indigenous nations ownership and jurisdiction over fisheries in rivers that flow through their reserves. Judges often refer to environmental factors such as geography and climate as a metric for an English statute’s applicability. The impact reception may have on environmental law, and its potential to shape the evolution of the field, offers just one example of the myriad legal, political, environmental, and social ramifications that hinge on the applicability of English law in BC.

Archival materials show that back in 1897 BC judges and legislators were attuned to the importance of settling the question of what English law applies in BC. Decisions like the 2013 SCC ruling, while aiming to clarify the rules of reception, simultaneously reveal how little progress has been made in this direction. In light of the significant impact these issues may have it is incumbent upon us today, at a minimum, to not overlook what existing efforts have been made to settle the matter.

- Centre for Law and the Environment